Why I didn't sell our startup to the highest bidder

How I grew resentful of my business and found an acquirer

Hi, it’s Melissa, and welcome to “your founder next door”, a bi-weekly column with stories of my human journey bootstrapping eWebinar to $5m ARR. No BS, just straight-up truth bombs on what it’s like to build a company without an abundance of resources or friends in high places.

The Big Aha! 💡

This is the story of why I didn’t chase the highest bidder when selling my startup, what I cared about instead, and the real reasons “founders next door” sell that no one talks about. It’s not the headline-worthy story you’re used to, it’s the human one that rarely gets told.

Backstory 👩🏫

I sold my last startup, Spacio, without hiring a banker, without doing the typical dog and pony show, without shopping the company to find the highest bidder. I didn’t even think about selling it until someone said they’d consider buying it.

Everything we read about makes us believe that founders sell their startups for that huge paycheck once they hit the peak of their game. In reality, founders sell their companies for a variety of reasons that never get talked about because their stories don’t make interesting clickbait.

For me, moving on from Spacio was the only way I could find joy in my life again. After spending almost a decade in the real estate industry, peddling software to agents who didn’t value technology, I grew resentful of the thing that was once my greatest passion.

I started the company because I had big dreams. I wanted to change the way open houses were done and upgrade the industry. I was naive about how difficult this mission was going to be and, on the road to finding that out, my business began to feel like a burden rather than a source of power even as it grew.

Getting into real estate 🏡

Growing up in Hong Kong, I always wanted to be a real estate developer because I was fascinated by the size of skyscrapers. I had no idea what it took, I just made that my ambition. After graduating from university in Vancouver, Canada, I worked for a luxury real estate developer as their receptionist. From there, I got my sales license and moonlighted for a residential properties marketing firm on weekends, helping sell pre-sales units at various showrooms. Eventually, I sold property full time and hosted open houses for lead gen every weekend. It’s safe to say that I was willing to get into the real estate industry at all costs.

After a few years in the business, I realized there were only two ways I could be a developer (one that built skyscrapers). The first was for me to be born into it, which wasn’t happening. The second was for me to marry into it, which also wasn’t happening. Okay I’m kidding…“marrying into it” simply wasn’t my destiny.

Discouraged and wanting to remain realistic, I left the business to pursue other opportunities in hope to find my next big thing.

The last job I had was at SAP, where I was an Inside Account Exec for large enterprises. It was my first big corporate job and I didn’t last very long for the same reasons that startup people don’t survive in corporate and vice versa. I wasn’t very good at managing my manager, but it was where I truly learned how to sell and for that, I am forever grateful.

I founded my first company, Flat World Apps in 2011. It was an agency where we built marketing apps on the iPad for real estate developers. Instead of being given a printed coffee table book about the building they were selling when you walked into a showroom, you could download the development project’s app and look at floor plans and galleries on an iPad. It sounds useful, but the iPad was new and didn’t have adoption, and the industry was never going to move past print. Every sale was an uphill battle. Anyone who’s run an agency knows that you’re either chasing the next sale or chasing the invoice. It sucked.

That startup did get me into real estate tech though…

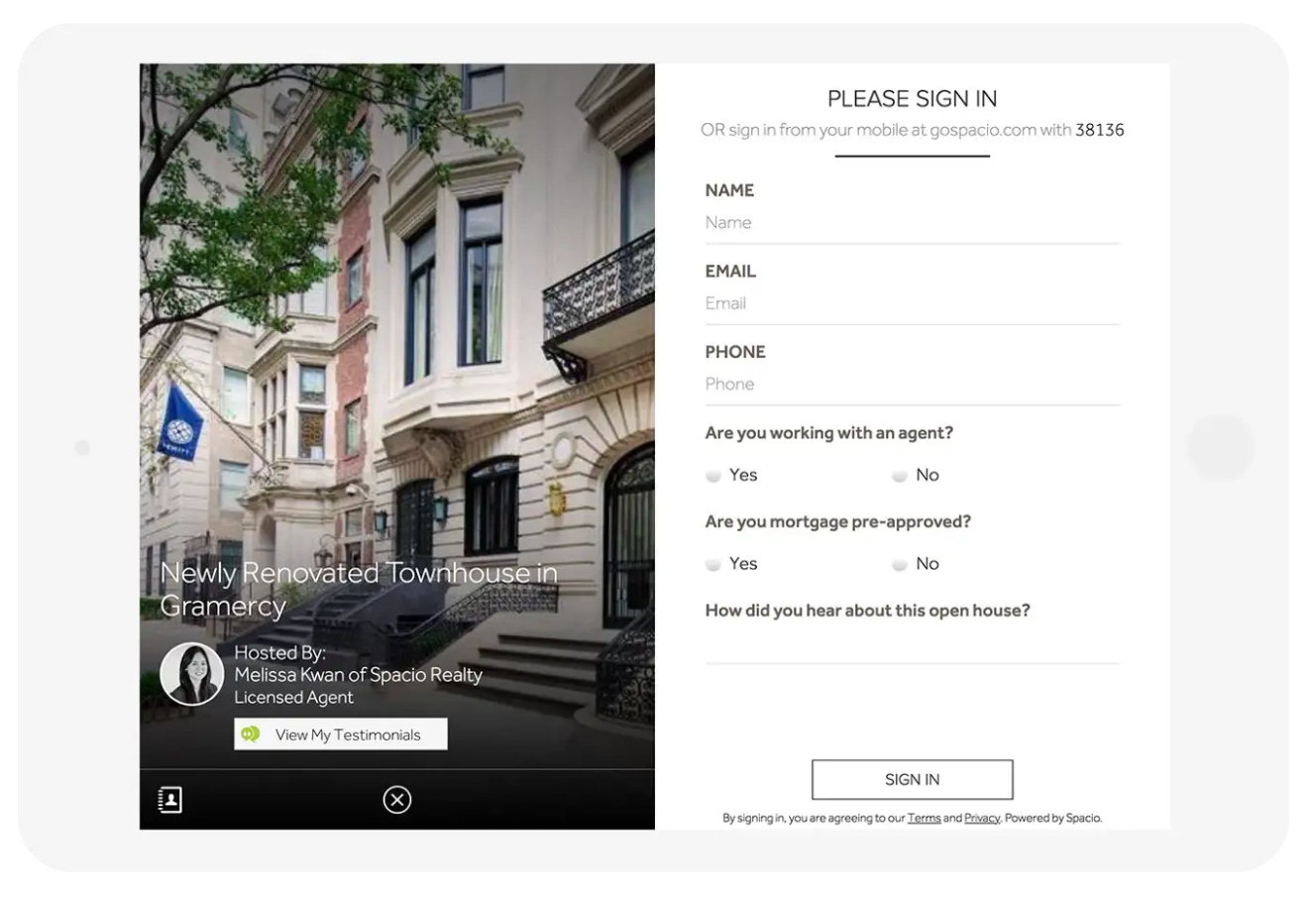

I started traveling to New York where the industry congregated, built a professional network, and eventually moved there to pursue bigger ideas. My first company transitioned into my second, Spacio, which was an open house check-in system – imagine instead of writing your name and contact info on a piece of paper when you walked into a property for sale, you’d type it into an iPad and then get an automated follow-up. That was Spacio. We were an enterprise SaaS solution that real estate brokerages (agencies) and franchises bought and offered as a perk to their agents.

For context, Flat World Apps lasted 5 years and Spacio was acquired in year 4.

👋 Before we continue - If you enjoy this article, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience?

This spreads the word and keeps me writing content that will inspire founders to keep doing what they’re doing, knowing they’re not alone.

How my business became my burden 😥

For the first 7 years of my founder journey, I never had any money. I always paid others before myself, and they only ever got 50-75% of their market rate. I got a loan against the revenue from the first company and put everything into the second company as starting capital.

I hugely underestimated how difficult it would be to come up with a product someone would pay for – it took Spacio 2.5 years before making our first $10. I burned so much capital in that time trying to find product market fit that we had to take on side projects to make ends meet. Surprisingly, we never missed payroll. I was living in New York with $100 in my account daily and would only pay myself enough to cover rent and immediate expenses at the end of the month. Bootstrapping forced me to learn to live with very little, much less than most college students. Thinking back, I have no idea how I did that. It was intense. I don’t recommend it. (I wrote about my darkest moment as an entrepreneur on this viral LinkedIn post.)

Reality had slapped me in the face and I finally realized how difficult it would be to make millions. All of those $100m exits I’d read about, what I thought was a rite of passage for every startup, was going to pass me by. I wasn’t cut out for it. I didn’t want work to be my whole life. I didn’t want the sacrifice. More importantly, our product didn’t possess the market potential to fulfill my startup dream. It was too niche and too geographically limiting as real estate is a regionalized business.

Spacio’s user base was made up of real estate agents, which meant our entire existence was dependent on how well they understood how to use the software so their companies would continue paying their bill every month. To say getting adoption from this audience was difficult is a massive understatement. Agents are notorious for being known as laggards in technology. They’re not a group that values it, and would rather spend $200 on a bottle of wine for a client than $20 on software that could help them capture another client. The average age of an agent is 55, and many have built successful businesses without tech. Admittedly, Spacio was more of a vitamin than a painkiller – every sale was hard, but after the sale was even harder.

I remember the days I was constantly responding to support tickets, feeling depressed from answering mindnumbing questions submitted by angry users—the same questions I had answered the day before, and the day before that, and the day before that.

“I forgot my password, can you send it to me?” (Use password reset.)

“I used Spacio and now my leads are gone!!! Fix this!” (Didn’t sync to the cloud.)

“Why can’t I login without internet? My open house doesn’t have service!” 🤦

I felt like I was spending my life trying to make real estate agents’ lives marginally better, and not being appreciated for it. What’s worse, I had convinced my cofounder to join me and knew we were never going to cash out on the dream I’d sold him years ago. I felt responsible for the outcome we weren’t going to get, which piled onto the stress I was already feeling from slow growth.

By the time we hit profitability on my meager salary, I was completely exhausted. Everything was a grind. From chasing invoices in Flat World Apps, to struggling to find product market fit with Spacio, to living like a college student, to begging customers to buy us and users to use us…

I was 37, and I was tired of having no money to live a normal life like my peers. Not taking trips with friends or ordering what I want at restaurants without always looking at the price first. I was tired of being in debt and of not knowing how to generate revenue fast enough.

I was tired of trying to convince people who didn’t value technology to buy our software. I was tired of supporting a customer base who didn’t understand the basics of how our solution worked.

I was tired of deluding myself that things were going to get better. I knew they weren’t, because we didn’t have the right business. The business was good, but it was never going to be great.

I was tired of seeing all the cool things happening out there that I couldn’t be a part of. The opportunity cost of staying where I was increased by the day.

I was tired of seeing the world pass me by.

I forgot how long this went on for, I just know that one day, I woke up and realized that I’d been hating my job, hating my life, and hating the trap I created for myself.

I remember a founder friend once told me, “You’re unable to feel the success for Spacio because you associate it with lack. One day, you’ll build something out of abundance and love, and everything will be different.”

He was right. Building Spacio took me to the lowest of the lows, and the highs were not high enough to overwrite the pain. Spacio was synonymous with my daily suffering, and nothing was going to turn it around.

I needed a change…

How we found our acquirer 🕵️

I never thought selling my company was an option. I didn’t think it was big enough or good enough to sell. I just wanted to get out, but I didn’t know how.

I hopped on a catch up call with my friend and mentor, Aaron Kardell, who was the founder of a mid-sized real estate startup called HomeSpotter. I met him years prior at the famous Zillow dinner I hosted, where I invited the CEO of Zillow to my house for dinner and used his name to fill the rest of the seats at the dining table. Aaron and I stayed in touch and would sync up every few months so he knew how I had been feeling for a while.

That day, I unloaded on him about everything and asked, “I wonder if my cofounder would let me sell my shares so I can do something else.”

To my surprise, Aaron responded, “If you’re serious, we’d consider acquiring Spacio, but you’d have to stay on for two years.”

I had no idea HomeSpotter was big enough to make acquisitions (we were their first transaction), and that they were on a path to get acquired themselves (they were acquired by Lone Wolf Technologies in 2021). Buying us was a part of that plan. I will write about the things that made Spacio an attractive acquisition in an upcoming article.

After sharing more about HomeSpotter’s strategy, Aaron asked me to think about what would matter most to my cofounder and I in an acquisition, and that would be our next follow up.

Things I cared most about in an acquisition ✅

By the time this conversation happened, Spacio was profitable, and I was nomading full time with David. After years of fighting for my freedom and bringing the company back from the dead, I knew I couldn’t give that up. What was most important for me was to preserve the lifestyle I had built, more so than the sale price.

This was pre-2020, so for most companies, working remotely was an earned privilege. At Spacio, it was a cost saving strategy turned lifestyle choice. Given Aaron and I had been friends for years, he knew this was non-negotiable.

Aaron knew how I felt about the business, the limits I saw, and that my heart wasn’t fully in it. But, from seeing what I’d done over the years, he also trusted that I would show up for customers no matter what, something I couldn’t have said about many other CEOs who would’ve expected me to at least double my efforts to make back their investment.

With Aaron, I didn’t have to pretend to be someone I wasn’t just to sell the company. This was the primary reason I didn’t go on a road show to pitch Spacio to a list of potential acquirers. I couldn’t imagine having to tell a story I didn’t believe, then continue to perform for a new CEO I’d sold that story to.

It’s important to note that because of our revenue (high 6-figures), we weren’t going to get blue-sky multiples from a bidding war. We might have been able to get more money by playing with the terms (cash vs. stock vs. earn out requirements), but every deal would’ve come with trade offs to my wellbeing which was my top priority.

It wasn’t about selling for the most money, it was about finding maximum happiness for myself, my cofounder, and our team. At the time, I just wanted to stop hustling and breathe a little.

The list of things I cared about most in an acquisition included:

A CEO I’d be happy to work for

A company that was well-respected

Ability to keep my nomadic lifestyle

Everyone getting (Canadian) market salaries

Company remains remote without strict office hours

Within a week of our follow up, Aaron made an offer and we started going through the process.

It wasn’t the exit I once dreamt about, but it was a good one that gave me the capital and confidence to start eWebinar on my own terms shortly after. More on that in the next edition…

Reflections 🪞

I sold my company because I wasn’t having fun anymore. I was able to sell it because it was a profitable business with low burn. When you have a good business, you don’t need to put on a dog and pony show to sell your company.

I wanted so badly for Spacio to be something, but it became something else instead. That something else created an emotional toll too heavy for me to carry.

When you say no to something that doesn’t bring you joy, you create space to say yes to something else that will.

Two months after the deal closed, I started eWebinar because I needed a new challenge and distraction. And because I didn’t sell Spacio for “retirement level money”, I knew I needed to get going with a new project if I didn’t want to work forever. Aaron signed off on allowing me to build eWebinar in parallel to working for HomeSpotter, and I fulfilled my two year contract there.

The biggest lesson I learned through all of this is:

You don’t have to keep pushing because it’s the “right thing to do”. You don’t have to sell to the highest bidder. Sometimes, you just need to move on for your own sanity.

👉 Read my next piece, a companion article to this one: What happened when my startup got acquired

Stuff mentioned in this article 👇

Forbes: How SaaS Founder Melissa Kwan Went From Burnout To Breakthrough

LinkedIn: This is the story of my darkest entrepreneur moment from the last 13 years in startups.

Thank you for reading!

— Melissa, your founder next door ✌️

Newsletters I follow (and think you should too) 🗞️

Dr. Julie Gurner: Ultra Successful - Insightful, easy to digest advice & executable strategies that makes you think, by a nationally recognized executive performance coach.

Kyle Poyar: Growth Unhinged - In-depth case studies and deep dives on pricing & packaging, go-to-market strategy, SaaS metrics, and product-led growth.

Greg Head: PracticalFounders - Weekly interviews with founders who have built valuable software companies without big funding.

Enjoyed reading this? Help spread the love 💜

If you enjoyed this piece and found it valuable, please consider sharing it with friends who you think would also benefit from this column. They can also sign up at melissakwan.com.

The only way this grows is by word of mouth, so I’d really appreciate all the help you’re willing to give. 🙏